Communicating Uncertainty in DFIR

/ 12 min read

Table of Contents

The room is near silent.

The CEO leans forward. “Was our data stolen or not?”

You take a breath. “We have been unable to confirm data exfiltration from the available evidence. Whilst we have not identified data exfiltration, it does not necessarily mean it did not occur.”

The energy drains from the room. Eyes glaze over.

You’ve just given the answer every investigator has delivered and every executive has hated. Technically accurate and practically useless for decision making.

I’ve been that analyst, more times than I’d like to admit.

A Confession

When I first started in DFIR, there were times when I believed that if I never fully committed to a position, I could never be wrong. My intentions were good; I wanted to ensure nothing I said could cause further impact to a client. My findings ended up being wrapped with phrases such as “most likely” and “from the available evidence”.

I started to notice that the businesses were making decisions during a time of significant stress without my clear guidance. The way I was communicating was placing a burden of interpretation on less technical individuals.

I realised I needed a better way to communicate uncertainty in a manner that was honest, useful, and did not end up in a court document as an example of what not to say.

This post is what I wish someone had told me earlier.

Overclaiming into liability

This overly cautious approach came from somewhere. It was to avoid the opposite, speaking beyond the evidence and causing decisions that make things worse. A recent Australian case offers a sobering example of this. During an investigation, a cyber security consultant stated the following.

When the consultant provided information on the ransom note:

…I don’t feel that this will happen and it is merely a scare tactic, however, to err on the side of caution I would suggest that you prepare a statement stating that there was a malware incident but no data has been exfiltrated nor lost and the incident is being controlled…

When the organisation asked the consultant whether it was necessary to obtain legal advice:

“…at the end of the day, this all goes back to the question, did the breach cause harm to any individuals? At the point where we ended our engagement, I would have to say no.”

The consultant concluded that there was no data exfiltration. Later, a posting appeared on a ransomware group’s leak site containing the client’s data.

What most likely went wrong? The consultant made a definitive statement when the evidence did not support that certainty. The consultant most likely spoke beyond their role. The investigation most likely had significant gaps. The evidence sources were most likely limited.

Notice anything with the above… I have very little idea about what actually happened within the investigation beyond the court documents, so I have hedged the sentences to signal my uncertainty and added room to be incorrect.

The Federal Court ordered the organisation to pay $5.8 million in civil penalties in relation to the data breach.

Source: OAIC v Australian Clinical Labs Limited

The Scenario

So we can walk through this together, place yourself within this scenario:

An organisation has experienced a ransomware incident. Your team is nearing the conclusion of the investigation. There is no evidence to suggest data exfiltration occurred. Firewall logs were rotated. Key system’s virtual hard drives were encrypted, with the latest backup being 7 days old. Your team has observed this group perform exfiltration in all previous incidents.

How would you go about answering the question “Was our data stolen?”

The Objective

We will never eliminate uncertainty in investigations, the real goal we are working towards is to communicate uncertainty in a way that enables effective decision making. The best DFIR professionals help organisations make good decisions despite the uncertainty. At the core of our role, we are there to guide an organisation through an incident… by being wishy washy with our wording, we are doing anything but that.

I’ve used three key principles whilst recording my thoughts on this topic:

- Be truthful and accurate.

- Enable the organisation to make informed decisions.

- Understand your role and its boundaries.

Understand What Is Being Asked

The questions you will be asked during an investigation are rarely pure forensic questions. Before answering a question, consider the decision that needs to be made behind the question. The decision behind the question may be something like:

- What am I going to tell the board or other executives this afternoon?

- What am I going to tell our employees and clients?

- Will we need to notify regulators and obtain legal advice?

Your response should change depending on the decision that is about to be made. Without understanding the underlying decision, your response can be misinterpreted.

For example, the response “we have not identified data exfiltration” may be heard as exfiltration is unlikely. From this interpretation, the CEO may communicate a response to clients. 2 weeks later, data is posted to a leak site. The organisation is now backtracking on statements which could have been prevented by the analyst seeking to understand the proper context. The response given was technically accurate, although the organisation still made an uninformed decision from it.

Separate Assessment from Recommendation

Separate your assessment from your recommendation to make a clear divide between the investigation facts and your guidance.

- Assessment: What do you think happened? How confident are you?

- Recommendation: Given your assessment, what should the organisation do?

These can point in different directions. You may have no evidence of data exfiltration while recommending that the organisation operate with the assumption that their data was stolen.

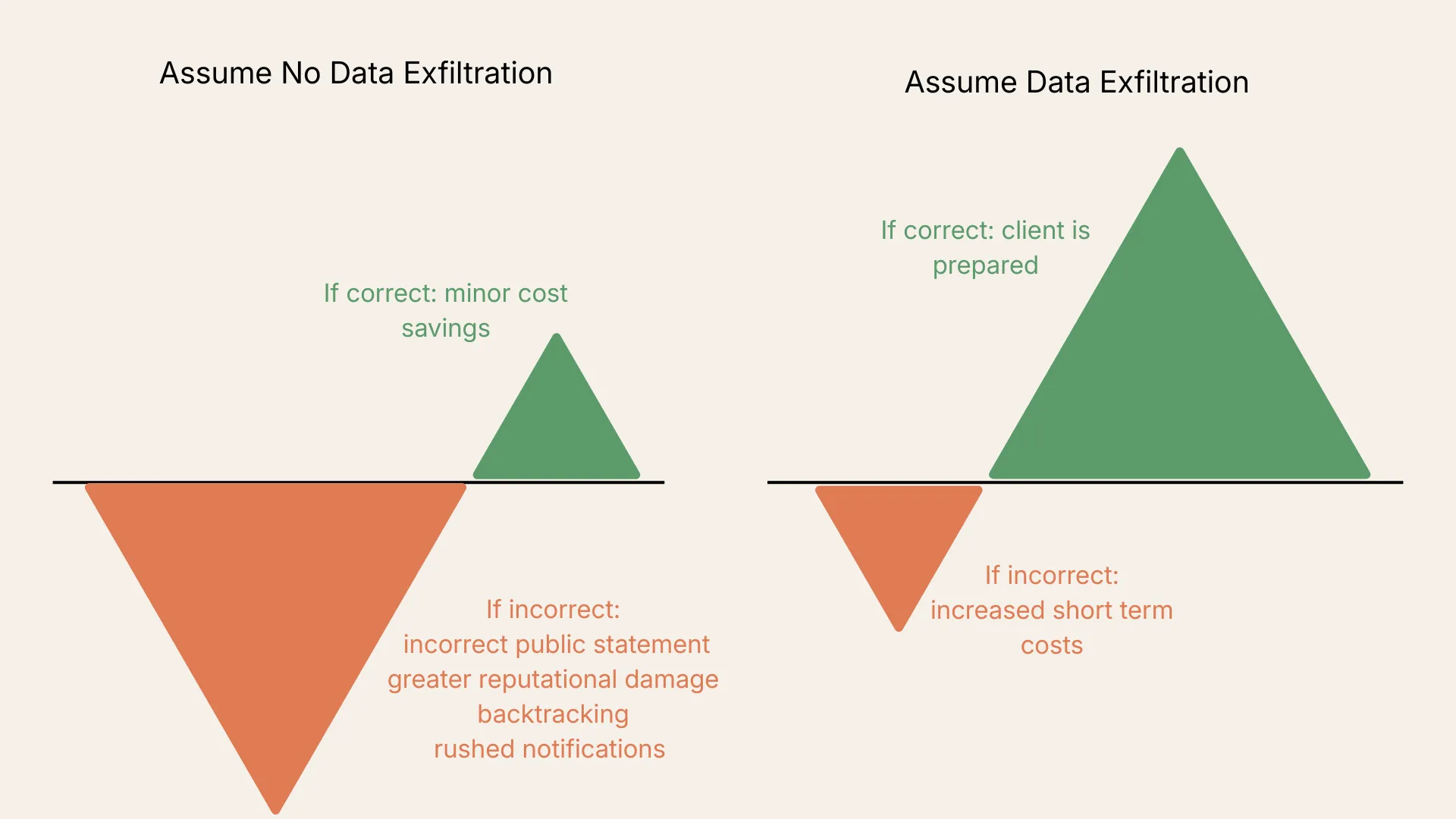

Why do this? Because the cost of being wrong in each direction is not equal. This is what’s called asymmetric risk.

Consider each direction:

- The business acts purely on investigative findings (no evidence of exfiltration = no exfiltration). If wrong, this results in incorrect public statements, greater reputational damage, backtracking, and rushed notifications after a leak site posting.

- The business operates under the assumption that data was exfiltrated, with no direct evidence. If wrong, the business incurs increased costs in communications preparation and stakeholder management. Although if a leak site posting occurs, they’re prepared.

Your assessment should be black and white aligned with the factual investigative findings. Your recommendation applies your experience to the various directions and approaches from your assessment. By separating the two, the idea is to outline your reasoning behind a recommended direction.

The business does not necessarily need to take a particular direction, as you have empowered them to make an informed decision with the proper context which includes your experience.

”Don’t Know” vs “Won’t Know”

Not all uncertainty is equal. There’s an important difference between what we don’t know yet and what we will not know.

- Don’t know: We’re still looking… the investigation may yield answers.

- Won’t know: The evidence is unavailable. No amount of investigation will answer this question.

These two positions require different responses. The first position requires patience whilst the investigation continues. The second requires understanding and guidance of the various directions and planning accordingly.

Being explicit about this helps clients understand whether more time will actually help and sets realistic expectations. It also protects you from the inevitable “why didn’t you find out?” question when the answer is “because the evidence no longer exists.” In our scenario, the limited firewall logs are a won’t know situation. No amount of investigation will help.

Name it directly: “This is a gap we cannot close. The evidence that would answer this question was overwritten before the incident was detected.”

Calibrating Confidence

When you say “likely,” what do you mean? What probability sits behind it and do you have a structure to remain consistent across investigations and with other analysts in your team?

The United Kingdom’s Defence Intelligence created a probability yardstick which splits and assigns terms to the probability scale. Academic research ensured each term is aligned with the average reader’s understanding of the term. Here is a quote from their webpage:

Intelligence analysts piece together assessments from an incomplete number of jigsaw pieces. Analysts therefore use a shared vocabulary of likelihood that aids clarity for both analysts and their readers, whilst communicating the probability that explanation or prediction is correct.

Doesn’t this sound extremely similar to our role! Applying the probability yardstick to DFIR may look something like the below:

| Term | Probability Range | When to Use in DFIR |

|---|---|---|

| Remote chance | 0% – ≈% | Evidence actively contradicts this conclusion. |

| Highly unlikely | 10% – 20% | Little to no supporting evidence. |

| Unlikely | 25% – 35% | Evidence points away from the conclusion, although can’t be ruled out. |

| Realistic possibility | 40% – 50% | Evidence is incomplete or inconclusive. |

| Likely / Probable | 55% – 75% | Evidence favours this conclusion. Limitations and meaningful uncertainty remains. |

| Highly likely | 80% – 90% | Strong evidence supports this conclusion. Small piece of the chain missing and/or alternatives exist although, are less supported. |

| Almost certain | 95% – 100% | Multiple evidence sources directly and strongly support this conclusion. |

There are deliberate gaps between the ranges. This is quite interesting as it forces you to commit to a direction rather than sitting on the fence in some cases. This also means you don’t have to use percentages in conversation.

In our scenario, what would you mark as the likelihood of data exfiltration?

I’d lean towards marking the likelihood of data exfiltration as highly likely. The Threat Actor has a known behavioural pattern, combined with the lack of evidence. The absence of evidence in this investigation is not evidence of absence.

If you’re leading a team, consider adopting the yardstick or a similar solution as a reference. You may consider including your own version alongside slide decks and reports.

Say What You’re Not Saying

In times of stress (also in general terms), human nature is to seek out what we want to hear. When you say “we have been unable to identify evidence of data exfiltration,” a hopeful CEO may translate that to no exfiltration has occurred. They’re looking for good news and they’ve found a sliver of hope through your wording.

You need to be aware of this and actively resolve it when you notice it. Of course, effective communication upfront can prevent this, although when it does happen, a useful technique is to explicitly name what you’re not saying.

Something along the lines of “I want to be clear about what I’m not saying. I’m not saying data exfiltration has not occurred.”

Yes, this is can be uncomfortable. You’re taking away the good news that the client was holding onto. The alternative is a lot worse: two weeks later, data appears on a leak site, and the CEO says, “You told us there was no exfiltration.” Now you’re explaining what you actually meant while the organisation scrambles to backtrack on their statements.

Being explicit upfront protects both you and the client. Most importantly, the organisation is making decisions based on the facts rather than the sliver of hope your wording gave them.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Let’s answer the CEO’s question: “Was our data stolen or not?”

The Wishy Washy Response:

We have been unable to confirm data exfiltration from the available evidence. Whilst we have not identified data exfiltration, it does not necessarily mean it did not occur.

A Better Response:

I recommend you operate under the assumption that your data has been stolen. We have worked on a number of cases involving this group and they’ve exfiltrated data in every instance. We are yet to identify evidence of data exfiltration within our investigation. Currently as we stand, my assessment is that exfiltration is highly likely. There are a number of limitations behind that such as the firewall logs being rotated and the way encryption was deployed. Operating as if your data has been stolen allows you to prepare as we continue our investigation.

Notice what’s happening:

- Recommendation

- Reasoning From Experience

- Assessment

- Limitations

- Recommendation Context

The client gets something to act on. They understand both your recommendation and your assessment. The limitations come after you’ve provided value for the purpose of clarity. The organisation may not follow your recommendation, although you’ve empowered them to make an informed decision with the proper context.

When You Simply Don’t Know

I am a big believer that it is okay to not know something. The key in those situations is to remain honest. Use phrases that build trust, such as:

- “I don’t want to give you the wrong information. Can you please leave this with me for a few hours? I’ll get back to you with an answer.”

- “That’s outside my area. I will leave that to [Name] to answer.”

- “We don’t have enough information to determine that yet. We will need xyz to give you an answer.”

Speaking Their Language

Technical accuracy means nothing if your audience doesn’t understand it. I’ve found analogies to be very useful to help explain technical concepts to non-technical audiences. Sometimes even some of the analogies I think of in the moment are a bit funky… in some situations, I’ve found that breaks the ice and brings a bit of humour during a time of stress. I’ve included a couple examples below:

Explaining file carving on encrypted hard drives:

Imagine someone ripped pages out of a book. We’re trying to find the remaining pages and determine if any of those pages have value to the investigation.

Explaining why a KRBTGT reset is needed:

All your accounts are made in a factory. There’s no point resetting the accounts if the key to the factory hasn’t been changed.

Explaining Log Rotation:

This is similar to reviewing footage from a security camera system after an incident last week, although the cameras only capture 24 hours of footage.

Reading the Room

This is the bad news: communication takes time. As you practice and improve, it will become a natural skill where you can read the room and adjust your communication style and approach accordingly.

The good news: communication can be learned, pay attention to the responses you receive and think over how you can improve the responses you provide. Watch other better communicators and learn from how they respond and handle different situations and individuals.

Final Thoughts

Cyber incidents are stressful, especially for those we assist who don’t experience them day in and day out. During stress, making good decisions is hard. Our job is to assist our clients not by removing the uncertainty, although standing alongside and helping them navigate an incident.

Keep these principles in mind:

- Be truthful and accurate.

- Enable the organisation to make informed decisions.

- Understand your role and its boundaries.